When you hear the name, "Maker Movement," what comes to mind? Maker Faires with complex gadgets made by kids who know more about physics and geometry than you? A cool club where only those who know about engineering and design can get in? 3-D printers and laser cutters and equipment that you or your school are not likely going to be able to invest in?

Sometimes we have this idea that the Maker Movement is something high tech and out of reach for average folks who may not consider themselves "makers." When encouraged to bring this movement into, say, an English language classroom, teachers may fear that they must suddenly become experts in science or technology or something outside their field. I'm here to affirm that this is not the case.

Science and math were never my strong points. Somewhere along the course of my study, I was told (or told myself) the lie that I (or girls in general) didn't have a "talent" for subjects science or math. Others were told the same story about art--that they're "just not good at it." I've come to learn that this presupposed attribution of talent simply isn't true. I also feel it's essential to change the narrative that some people are better at certain things. Of course, some folks may have a natural inclination or aptitude for certain fields, but it takes all kinds of people to come together to put the letters in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, Math). It's communication and collaboration that bring them together. These are skills we teach in English language classes.

Although I may at times regret giving up too easily on deeper study of math and science, when I bring a STEM or STEAM challenge to my students, I am confident in my role simply as an English language teacher. This is true whether my students are making a structure that needs to withstand a gelatin earthquake to reflect on using past perfect or adverbials, or making catapults and speculating about how their design could be better, using unreal conditionals. I am teaching the grammar and giving them tools to communicate. They are figuring out design and engineering. This may be by trial and error, combined with teamwork. Or by choosing from a few options of suggested models that I provide. It may also involve them pulling out their phones and doing the research themselves. English course books have texts and discussions on all kinds of topics that are outside of my field. That doesn't intimidate me. Neither should a STEM challenge.

At the end of the day, my goal isn't for students to know all there is about weight distribution or achieving the perfect projectile. I want them to be able to use the target language in a dynamic activity. I want them to learn to communicate and collaborate with other people. I want them to find ways to problem-solve creatively. I want them to do the hard work of critical thinking. If they can practice and learn some STEM/STEAM skills while doing that, all the better. The focus, however, is on solving a problem, bringing something into existence that wasn't there before, and doing it with the tools--physical tools and language tools--provided.

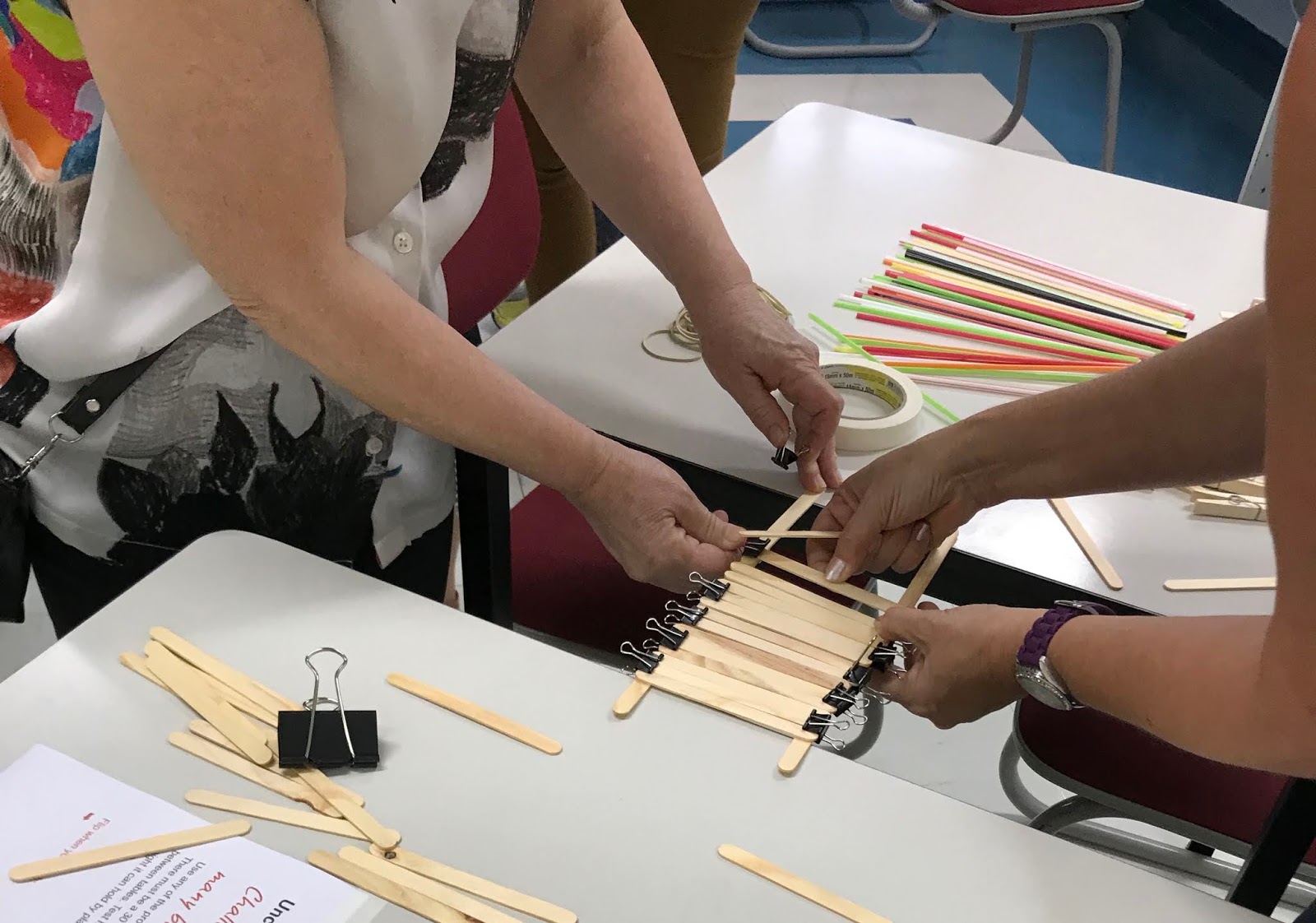

I don't use a lot of high tech stuff. Craft sticks, masking tape, binder clips, clothes pins, rubber bands, cups, and straws are some of my go-to materials. Smartphone technology does make things like virtual and augmented reality easily accessible for the classroom, and there are many web apps that allow students to make animations, comics, and even code their own video games, all for free. Little by little, I learn, along with my students, how to use these and what can be done with them. The result is students using authentic English to collaborate and problem-solve, and, often stretching themselves, to discover what they are capable of, all while making something meaningful.

In part one of this series, I mentioned that if I'm the only source of knowledge for my students, I'm actually selling them short. That's true if they depend on me to be their dictionary in class, and it's also true if I think I need to be the one to teach all the STEM skills. Instead, why not foster collaboration by putting students in pairs or groups where one student's knowledge and abilities will complement that of the other? Why not encourage independence by challenging them to find the answer themselves--in the book, on the Internet, or from their peers?

Whether inviting my students to collaborate on a school-wide project, represent an important concept in the form of a created object, or engage in a mini collaborative STEM challenge, I am also aiming to foster an environment where creativity can thrive and ideas can be explored. My goal is to empower young people, not only in English language skills, but in preparing them for a world that needs creative problem solvers with the soft skills to collaborate with people of different backgrounds and take on complex problems that seem to be changing by the minute. This is a world that needs makers more than ever. It's by making, in low-stakes challenges, finding solutions with peers, using the tools at hand, that people can discover their voice. Not all of us are going to be engineers or designers. But we're all citizens of this world, and, together, we're responsible to start solving its problems, one piece at a time. The reality is, we are all makers.

Comments